Artist Sasha Serber’s exhibition Not From Our Side originated with an offer for a solo exhibition. With the aim of enriching the dialogue regarding the content that interests him in his work – questions of image and myth relating to the figure of the hero and the anti-hero in Israeli culture in general, and in the context of immigration in particular – Serber decided to “host” the works of artists Boris Schatz and David Wakstein. Serber continues a fairly long tradition common in Israeli art especially from the 1960s onwards – years that marked a turning point when by degrees the hero lost his heroism, until he became an anti-hero. This revolution, given expression in literature and poetry, in play writing and the visual arts, created a barrier between the rebellious Israeli art and Israeli society that still educated its children on values embodied in the image of the hero.

Nicht Fin Unzara | Sasha Serber, Boris Shatz, David Vakshtein

Tavi Dresdner Gallery, Tel-Aviv, March 2008In a society that still lives by the sword, current affairs continue to influence the world of art as well, and dealing with the image of the hero is still relevant. The artistic debate that began fifty years ago continues to develop, becoming more sophisticated, while methods of expression, raw materials and artistic styles change.

Serber, born in Moldova (the former Soviet Union), immigrated with his family to Israel in the early 1990s. The experience of immigration and displacement present in his work is recognizable. In the current exhibition he examines his attempts as an immigrant to integrate into the local art scene as well as into Israeli society in general. His gaze is distant and analytical, almost free of emotion and subjective expression. As an immigrant, on the seam between belonging and not belonging, yearning to become part of the culture and society in which he now lives, and unwilling to relinquish the rich culture he belonged to, leads him to cast a critical gaze at the founding myths of Israeli society. By dealing with “Diaspora-like” subjects and familiar images from the world of comics, Serber examines the question of whether an immigrant can establish himself as a local hero without giving up his foreign aspects. He shows the comic hero Batman over and over again, employing different techniques of working (wood carving, wood etching, copper engraving, drawing with a felt- tipped pen, pencil sketches, woodcuts). Serber ”employs” this iconic image (a creation of American culture) to ridicule the human tendency for hero worship. He describes Batman’s image using classical, monumental, heroic methods of representation in the best traditions of the art academy in Kishinev in Soviet Russia that he was reared on. This school for realistic art tended to follow classical art sources (Greek, Roman and the Renaissance) aiming to reach a perfection of expression, and a realistic imitation of what the eye sees. Serber applies his classical technical skills to address local/current subject matter that concerns him, and through their use examines the relationship between the original image, which he exhibits, and its various incarnations.

Along with Serber’s works is a sculpture by Boris Schatz – also an immigrant, yet someone who situates himself as a typical representative of the heroic Zionist concept. Schatz (a visionary, founder and director of the “Bezalel” School of Art – a Jewish art school in Jerusalem founded in 1906 and named after Bezalel Ben-Uri the biblical artisan who designed the Temple and its ritual objects) reflected in his works the Zionist ethos, which represented a worldview that merged the national, philosophical, artistic and social utopia of the early 20th century in the country. For this exhibition a bronze sculpture by Schatz portraying the hero Samson was chosen. What is interesting in this work is that the mythological Jewish hero is shown not in a moment of “heroism” but specifically in a moment of anti-heroism – when he is bound with iron chains, bowed and defeated. In a similar manner, the character of Samson appears in the poem of Yehuda Amichai “Samson,” in which the poet presents himself as one who “ Every fortnight I go/ to cut my hair/Every fortnight/ my strength is taken away.” Amichai portrays Samson as a hero who has become impotent. “ I bring down their temples/nothing happens/ nor are there injured.”

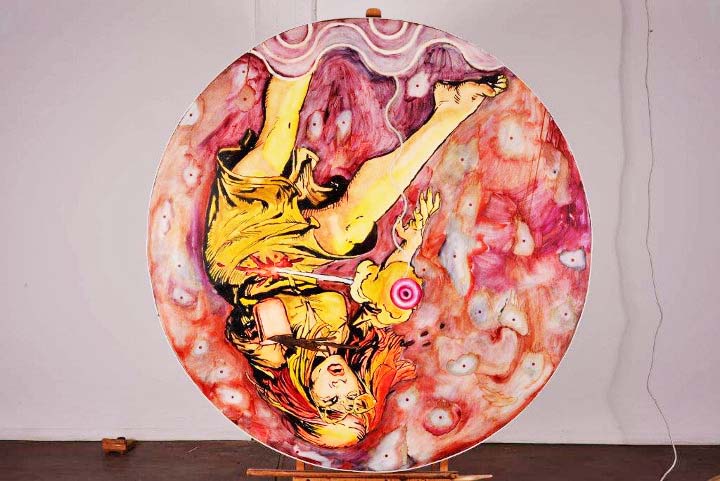

Joining this dialogue between Serber and Schatz concerning the nature of the hero’s image are the works of David Wakstein, who calls his style of painting “hot-tempered and talkative” and marks the artist’s role in society as a prophet of doom, a healer and educator. Wakstein’s works (similar to those of Serber) describe figures taken from the world of comics. However, Wakstein shifts his point of view to the victims of heroes. Two of his circular works using the technique of oil on canvas, show images taken from a comic book of the 1980s. The circular format of the canvas is reminiscent of a drop of blood, a dartboard, a teardrop or bullet hole. In both of them the same feminine figure wounded by a bullet from the gun of a familiar super hero is seen. The frozen moment of being injured in fact accentuates the movement of the body thrown backwards from the blast of the impact. In the context of these works Wakstein discusses the desire to invent a unique artistic language without bowing to the traditions of realistic painting. To paint a ”popular” painting with “highbrow” visual art values. Using the language of comics, claims Wakstein, allows him to touch on human existential values directly and authentically without resorting to cold formalism.

“The strategy of using comic illustration allows me to say something simple in a clear and unequivocal way that I would not be able to say using a realistic style of painting. In fact I talk about Israel’s wars using the strategy of a little boy who is an American comics enthusiast. As one born on a kibbutz, a casualty of war, I remain an outsider, trying to push my way in and to create a place for myself in the realm of art as well”…

Tavi Dresdner Gallery, Tel-Aviv